how to make a living as a costume designer

Costume Designer's Goals

Costume design is the most personal aspect of design. The costume designer must create clothes for characters that, on the one hand, reflect the ideas and goals of the play, but, on the other hand should look like the character chose the clothing in the same way you choose yours every day. Similarly, because we all wear clothes but probably do not design houses, audiences and actors will make strong, personal associations with what a character is wearing on stage.

The costume designer's goals are similar to the set designer's goals. These goals can be broken into five categories: costumes should help establish tone and style, time and place, and character information, and costumes should aid the performer and coordinate with the director's and other designers' concepts.

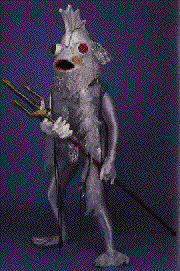

Costumes give information on the tone and style of a play. They may look just like what we wear today, or they may look like what people really wore at the time in which the play is set. Both of these would be illusionistic costuming. On the other hand, costumes might be representative of an idea in the play; for example, actors costumed in robes or unitards of various colors will establish a theatrical style. A different, stylized approach to costuming might also use some period elements mixed with contemporary dress; this would give the audience a flavor of a historical period without trying to create a full, theatrical illusion of another time and place.

Costumes tell us a great deal about the time and place in which a play is set. Dresses with an empire waist made of light fabrics in light colors place us in the early 18th century, such as in Jane Austin's novels. Blue jeans with bell bottoms and painted or embroidered with many bright colors tell us a character belongs in the late 1960's.

Dresses with an empire waist made of light fabrics in light colors place us in the early 18th century, such as in Jane Austin's novels. Blue jeans with bell bottoms and painted or embroidered with many bright colors tell us a character belongs in the late 1960's.

Costumes give us information on individual characters, on the relationships among characters, and on groups of characters. First consider your own wardrobe, and what you would choose to wear on a job interview, on a big date, to wash the car, or to come to class. What you wear says a great deal about who you are and about what you are intending to do. The same is true on the stage, but on stage we make even more associations with a character's clothing because we know it is specifically chosen for the play. If we see a woman on stage in a bright red dress, we will make associations with the dress's cut and color. For example, we might decide that the character is dressed for a night on the town. We might associate either passion and love with the red color, or perhaps blood and violence, or perhaps images of the devil. If other characters on stage wear subdued tones or cool colors, then the character in red will contrast with the other characters. On the other hand, other characters in shades of red will be visually linked the character in the red dress. Similarly, characters will be visually linked on stage if they wear clothing with similar silhouettes or colors.

The costume designer works closely with actors. He designs costumes for that specific actor's body as much as for the role the actor is playing. For example, if a designer had planned the red dress mentioned above for the central female character in a play, but the director casts a woman with orange hair and freckles, the red dress will no longer have the intended effect when worn by that actress. A more complimentary color will be chosen. Similarly, costumes can be used to enhance an actor's height, girth, natural coloring or to draw attention to any part of the actor. In the end, the actor must be comfortable wearing her costume: the work of the actor and of the designer can be undermined if an actor is uncomfortable in the clothing or does not know how to wear it and move in it correctly. For example, actors today must practice walking around in full length, hooped skirts or in a top hat and tails so that the character can appear to the audience to be comfortable in such clothing.

Finally, the costume designer must support the director's concept and must work with the other designers to create a coordinated visual effect.

Costume Designer's Tools

Like the set designer, the costume designer has two sets of tools: the elements of visual design and the practical material needed to create costumes.

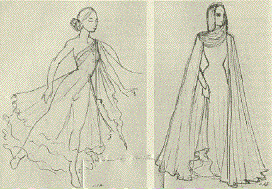

As discussed in the last chapter, the elements of visual design are line, mass, composition, space, color, and texture. The costume designer uses the design elements somewhate differently from a set designer. The first important element of a costume is its silhouette, which combines its line and mass. Silhouette is the fastest way to identify the time and place of a period costume. Silhouette also tells what parts of the body are emphasized, hidden, or displayed by the clothing. Contrast a Restoration woman's silhouette with a woman dressed to go out today: the Restoration woman wore an enormous skirt with underskirts and panniers to increase its mass yet wore a bodice with an extremely low, wide neckline; the woman today might wear a mini skirt, heels, and blouse emphasizing the length of her legs. The Restoration woman would never show her legs, while few contemporary women would dare wear a Restoration neckline.

Silhouette is the fastest way to identify the time and place of a period costume. Silhouette also tells what parts of the body are emphasized, hidden, or displayed by the clothing. Contrast a Restoration woman's silhouette with a woman dressed to go out today: the Restoration woman wore an enormous skirt with underskirts and panniers to increase its mass yet wore a bodice with an extremely low, wide neckline; the woman today might wear a mini skirt, heels, and blouse emphasizing the length of her legs. The Restoration woman would never show her legs, while few contemporary women would dare wear a Restoration neckline.

A costume designer considers composition on several different levels. She composes a single costume, she creates a composition of a single character over the duration of the play, and she composes how the entire cast should look when on stage together at any moment of the play. Usually a central character will change radically through the play's action (Oedipus blinds himself, Nora in A Doll House decides to leave her husband) and the character's successive costumes should show the character's evolution. Factors that a costume designer considers when composing the costuming of the entire cast might include putting the leading characters in more noticable clothing, working within a restricted color pallette, or demonstrating relationships among characters through silhouette or color so that some look good and some silly together.

Space is less a factor for costume designers than set designers, because their canvas is always the human body. Color in costumes functions similarly to color in set design; it has its four properties, we associate certain colors with comedy versus tragedy or with other kinds of moods, and color must be used with less subtlety than in life to compensate for the distance between audience and actors.

Texture in costume is slightly different from set design. The first element of texture is in the fabric itself: satins are smooth and shiny while lace is light and highly textured and tweed is heavy and highly textured. On the stage, plastics, leathers, furs, feathers, and other materials may also be combined with fabric. Two dimensional texture is provided by the fabrics' patterns: paisley, plaid, and polka dots have a busy visual texture, for example. Many costumes are composed of multiple fabrics making up multiple articles of clothing plus accessories, making an elaborate visual texture.

Two dimensional texture is provided by the fabrics' patterns: paisley, plaid, and polka dots have a busy visual texture, for example. Many costumes are composed of multiple fabrics making up multiple articles of clothing plus accessories, making an elaborate visual texture.

Movement is an element of visual design only in art forms that move through time (video, film, theatre, kinetic sculpture) Costumes must move with an actor through space, and the amount of movement should reflect the character and action of the play. Light or loosely woven fabrics move more freely than heavy or tightly woven fabrics or than other costume materials like leather or plastic. Consider the Romantic ballerina's tea length tutu of gauze versus the armor worn in a Shakespearean history play.

Practical Tools

In a more practical sense, the tools of the costume designer are the fabrics or other materials out of which costumes may be created; the various methods of putting costumes together, such as sewing machines or hot glue guns; and the bodies of the actors themselves, because no costume will make it onto the stage without an actor in character in it.

and the bodies of the actors themselves, because no costume will make it onto the stage without an actor in character in it.

To Costume Design Part 2

BACK TO BLOOD'S COURSE MATERIAL HOME PAGE

how to make a living as a costume designer

Source: https://www.geneseo.edu/~blood/CostumeDesign1.html