10. explain what factors have contributed to increasing real wages over time.

The expectation of ascent living standards, with each generation doing improve than the 1 before, has long been a given. More recently, that expectation has diminished—and with good reason. 1 of the best measures economists utilize to determine Americans' economical advancement is whether wages are rising, broadly and consistently. After adjusting for inflation, wages are just 10 pct college in 2017 than they were in 1973, with annual real wage growth just below 0.2 percent.1 The U.S. economic system has experienced long-term real wage stagnation and a persistent lack of economic progress for many workers.

For more than than a decade, The Hamilton Project has offered proposals and analyses aimed at increasing both economic growth and broad participation in its benefits. This document highlights the necessary weather for broadly shared wage growth, trends closely related to stagnation in wages for many workers, and the contempo history of wage growth, with an accent on the experience of the Great Recession and recovery. It concludes past discussing how public policies can effectively contribute to the growth in wages that is a core office of improving living standards for all Americans.

Full introduction

What is necessary for broadly shared wage growth?

The economic forces that underlie wage growth—that is, the increase in pay going to typical workers—essentially comprehend all aspects of the economy. Wages depend on how productive workers are, the share of economic output that is channeled to bounty, and the segmentation of wage and nonwage bounty (including benefits like health insurance). Workers' productivity, in plow, depends on the human being and physical upper-case letter used in the production process, as well equally how efficiently labor and capital are used.

For the inflation-adjusted bounty paid to a typical worker to ascension sustainably, a number of conditions must be met. Workers must become more productive over time. They must have adequate bargaining ability such that their share of the returns to production remains stable or increases. And labor income has to exist broadly shared, rather than concentrated at the superlative.

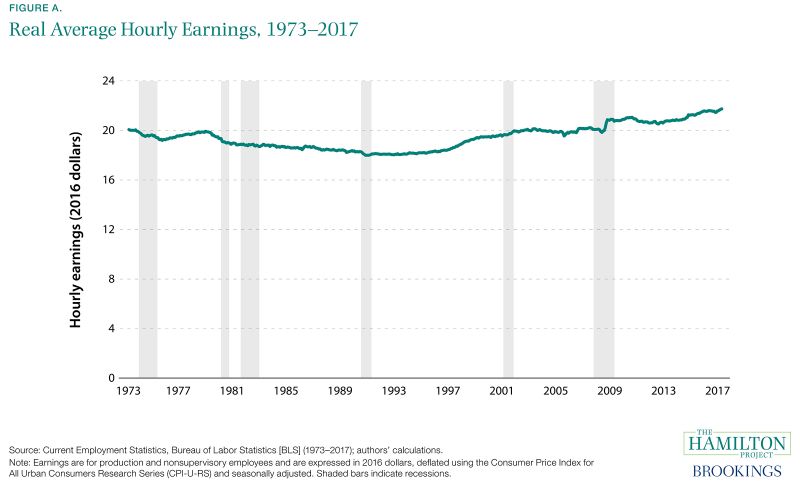

Effigy A reflects the many economic forces that contribute to wage trends. Real wages fall over some periods because technological progress slows, upper-case letter investment weakens, nonwage benefits increase, or because labor receives a diminishing share of economic output. Over short horizons, wages can exist influenced by simple supply and demand for labor: a weaker economy tin yield insufficient need for labor, generating weak wage growth. Besides, unexpectedly high aggrandizement tin pb to steep drops in real wages, every bit in 1980, and unexpectedly depression inflation can lead to an increase in real wages, equally in 2009.

Box 1. What'south in a Wage?

A number of different concepts are often lumped together under the term "wages." It can refer to greenbacks earnings or full compensation, including benefits similar wellness insurance. Information technology tin can be measured at an hourly, daily, weekly, or annual frequency. In different contexts, i might refer to boilerplate wages or to median wages, with the latter corresponding more closely to the experience of a typical worker. Finally, wages can be expressed either in nominal or inflation-adapted (real) terms, accounting for changes in prices.

Depending on the question that is existence asked and the data that are available, nosotros alternate between these various wage definitions in this document. When differences between the definitions are economically important, we highlight the distinctions and discuss their relevance. Nosotros mostly emphasize existent wages or compensation considering they describe changes in the purchasing power of workers.

The Importance of productivity Growth

For workers to experience ascent living standards over whatsoever substantial period, labor productivity must likewise ascent. That is, for a worker to be paid more than for an 60 minutes's work, the value of that worker's economical output must increase.

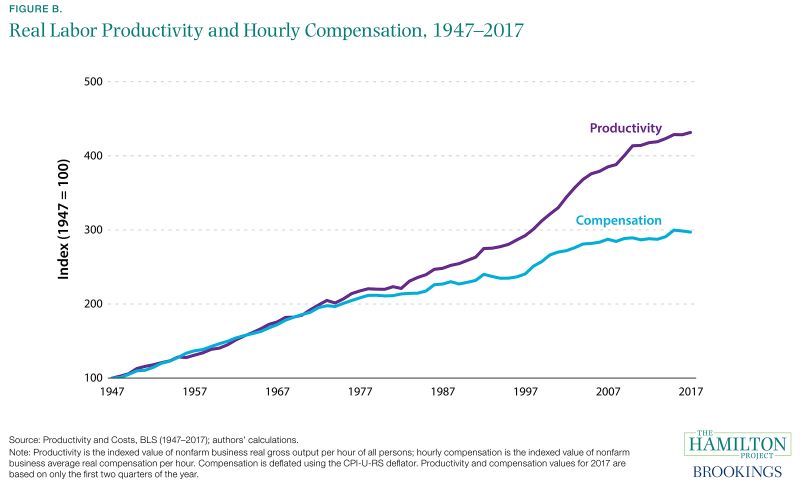

The history of the U.South. economy has been one of rise labor productivity, equally shown in effigy B. Technological advances, increases in homo and physical capital, and improved concern methods allow for dramatically more efficient uses of man labor as those advances and improvements accumulate over time.

Wages rise in the wake of these changes because firms compete with each other to rent and retain those workers who have become more than productive. Figure B shows the increase in output per hour (productivity) and average compensation per 60 minutes—both adjusted for inflation—from the postwar catamenia through the nowadays. Both serial accept exhibited large increases over that flow.

What economic and policy factors might reduce compensation growth by limiting worker productivity? In subsequent capacity, we explore a number of possibilities. First, worker mobility—both across jobs and beyond states—has been in turn down for decades. In add-on, business start-ups have become less mutual. These developments are associated with weaker increases in productivity and wages, given that they limit the reallocation of workers to productive new jobs. Finally, the recent decline in the growth of upper-case letter relative to labor depresses workers' productivity.

Who benefits from productivity growth?

However, even robust growth in productivity is not always sufficient to ensure ascension wages, peculiarly for workers at the bottom and heart of the wage distribution. Two considerations are most important.

Starting time, the overall share of economical output that is received by workers can and does change over time. For example, if the share of output received as wages and benefits falls, real wage growth that would otherwise have occurred equally productivity improved might diminish or even disappear completely. This dynamic affects workers equally a group, rather than the distribution of wages received by various workers. Changes in worker bargaining power, competition within and across industries, and globalization tin all influence the share of output workers receive. Over the long run, labor's share of output has fallen, which is reflected in the fact that average compensation growth has lagged behind productivity growth (every bit depicted in effigy B).2

Second, the inequality of wages paid to workers tin can as well change over time. While workers as a whole might benefit from productivity growth over some period, these benefits are sometimes shared unequally. Indeed, real wages for those in the bottom half of the wage distribution take stagnated since 1979 (the primeval year in which appropriate data are available), whereas the upper reaches of the distribution accept seen big gains. To the extent that labor'south gains disproportionately accrue to those with high incomes, gains for the typical worker will lag even farther backside productivity growth.

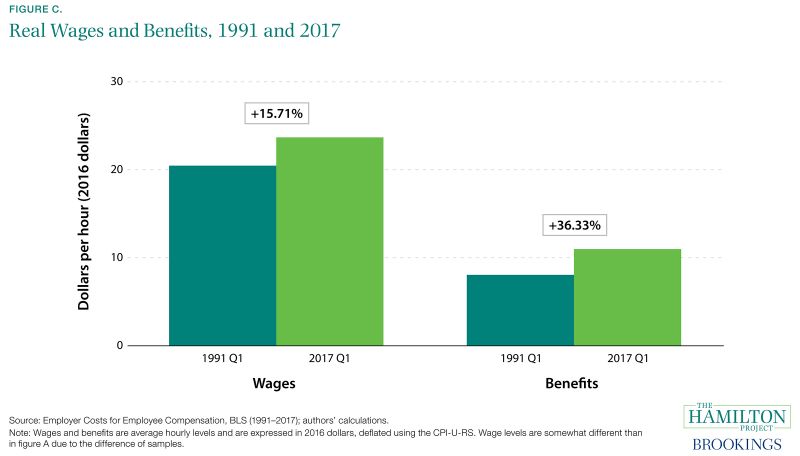

Finally, wages are only one component of compensation: nonwage components—such equally health, life, and disability insurance, every bit well as retirement contributions—might take up a falling or rising share of compensation over time. To shed light on these trends, figure C shows growth in wages and benefits separately. While benefits take made up an increasingly large share of compensation, wage growth has lagged.

Economic and policy changes are both of import for the division of economic gains. In the adjacent affiliate nosotros explore the roles of technological progress, globalization, and changing returns to education in driving some of these wage trends over the long run. We also examine declines in the charge per unit of union membership and the real minimum wage, focusing on how these developments have affected the level and distribution of wages.

Chapter ane: Why have wages been stagnant for so many workers?

Fact 1: The share of economic output workers receive has generally fallen over the past few decades.

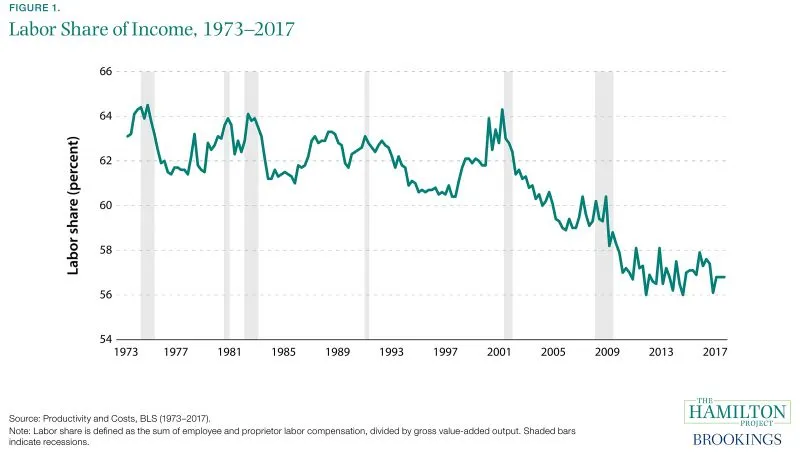

Long-term wage stagnation tin be traced to many trends, including the decline in labor's share of income. The portion of national income received by workers fell from 64.5 percent in 1974 Q3 to 56.viii percent in 2017 Q2. Over the past few years the U.S. labor share has ceased falling, just this might reverberate the ongoing economical recovery rather than any modify in the long-run downward tendency.

The fall in labor'south share is non unique to the United States. In other advanced economies, it has also been falling since the 1970s. The declining labor share has been traced to both technological progress every bit well as to the increase in majuscule intensity of production (International monetary fund 2017; Karabarbounis and Neiman 2014). Analysis has suggested a number of other possible explanations for the U.s.a., including the offshoring of labor-intensive production. A portion of the labor share pass up is likely due to difficulty in measuring labor compensation (Elsby, Hobijn, and Sahin 2013; Smith et al. 2017).

Ane recent study suggests that the autumn in the labor share is related to the rise of so-called superstar firms, which the authors argue are likely to have lower labor shares given their high profitability (Autor et al. 2017). Market concentration has increased noticeably over time and could be playing a role in lowering labor'southward income share (Furman 2016).

Fact 2: Wages have risen for those in the top of the distribution but stagnated for those in the bottom and centre.

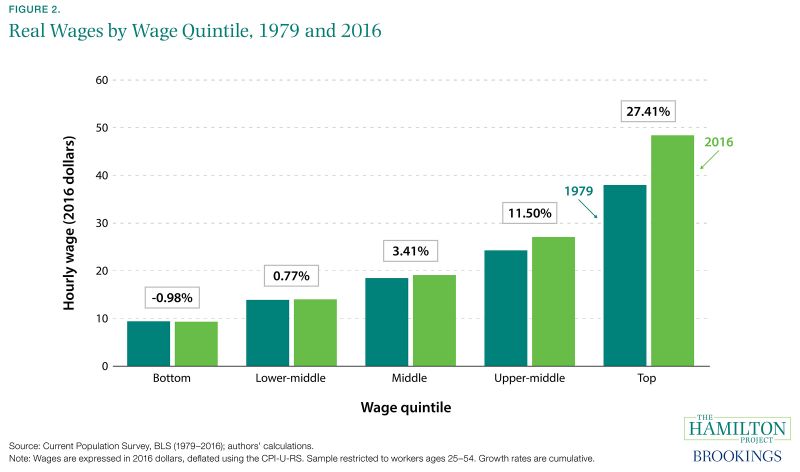

Wage inequality has been on the ascent over the past several decades. In figure ii we examine wages rather than total compensation, which include nonwage benefits. (Compensation has likewise exhibited increasing inequality; run into Pierce 2010.) This permits a sharper focus on wages, which are of item interest to many workers.

Much of the growth in wages has been concentrated at the top, with wages in the top quintile growing from $38 per hour in 1979 to $48 per hour in 2016—a 27 percent increase. Wages in the upper-middle quintile increased by 12 percent, from $24 per hr to $27 per hr. In the bottom fifth, real wages fell slightly over the same period.

Contempo research has shed calorie-free on how inequality is evolving between and within firms. For smaller firms, the ascent in wage inequality has largely occurred across businesses, rather than within: some firms systematically pay college wages than others. Past contrast, wage inequality within the largest firms has increased considerably (Song et al. 2015).

Some researchers have tied increases in wage inequality to globalization (Haskel et al. 2012), while others accept explored the role of technological progress (Autor, Katz, and Kearney 2008; Goldin and Katz 2010). Labor market place institutions, discussed in fact half-dozen, accept also had important furnishings on the distribution of wages.

Yet, widening inequality has not ever been a feature of the U.S. economy. Equally contempo piece of work by Piketty, Saez, and Zucman (2016) has shown, overall income growth (including both labor and capital income) was tilted toward the lower end of the distribution from 1946 through 1980. Incomes rose faster in the bottom half of the income distribution than in the pinnacle x percent or top i per centum. Since 1980, that procedure has clearly reversed.

Fact iii: The education wage premium rose sharply until about 2000, contributing to rising wage inequality.

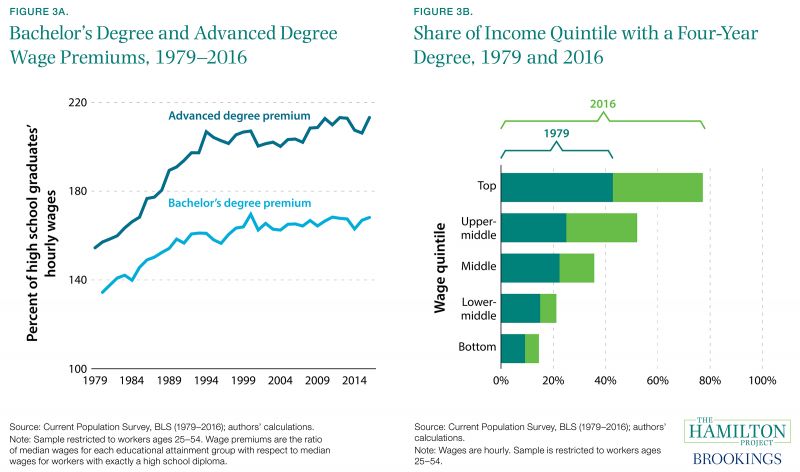

The wage benefit to a college degree increased remarkably during the last two decades of the 20th century, leveling off around 2000 at a historically high level (see figure 3a). Bachelor'south degree holders ages 25 to 54 in 1979 could expect to earn 134 percent of the wages received past those with just a high schoolhouse education, and advanced caste holders could look to earn 154 percent. By 2016 the wage premiums for a bachelor'due south degree and an advanced degree had risen to 168 and 213 percent, respectively.

At the aforementioned time, the percent of workers with at least a four-year higher degree also rose dramatically—from 23 percent in 1979 to twoscore percent in 2016. As shown in effigy 3b, workers beyond the wage distribution have become more than educated, but the increases have been larger for those with college wages. Workers with a college education are now the bulk in the top ii income quintiles: their shares doubled or nearly doubled from 1979 to 2016. Past contrast, college-educated workers represent just fifteen percent of the bottom quintile. These changes in college attainment and the college wage premium reflect an evolving mix of individuals attaining college degrees likewise as shifts in the relative demand for loftier-skilled labor (Abel and Deitz 2014).

Because wages roughshod for those workers with but a loftier school diploma, the increase in educational attainment did non atomic number 82 to sharply rising wages for the typical worker, despite the education wage premium and rising attainment. Nonetheless, increasing educational attainment still further could have important economic payoffs. By one estimate, increasing men'southward college attainment by x percent would eliminate near all of the reject in median almanac earnings observed from 1979 to 2013 (Hershbein, Kearney, and Summers 2015).

Fact 4: Globalization and technological change have probable put downward force per unit area on less-educated workers' wages.

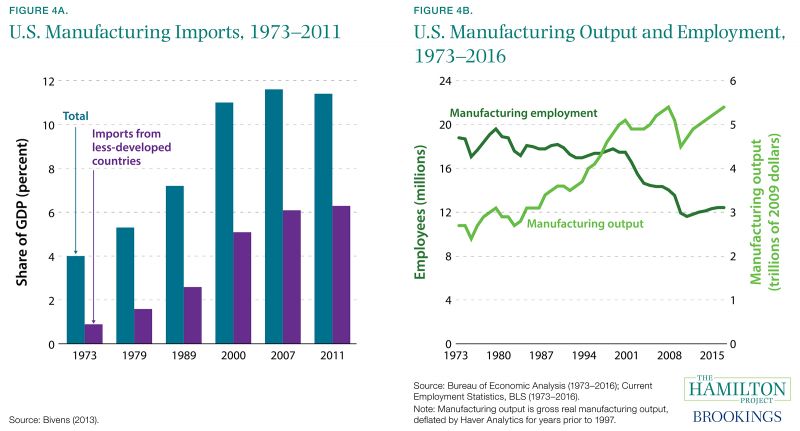

While theory and bear witness suggest overall gains to an economic system when opening to trade, some groups may suffer negative consequences. Basic trade theory implies that when a country with arable capital and loftier-skill workers (like the United States) trades with a country abundant in low-skill labor, lower-skilled labor in the rich country will experience losses (Stolper and Samuelson 1941). Equally seen in effigy 4a, the U.s. imports more manufactured goods today than in prior decades, an increasing share of which has come up from low-wage countries. Recent work focusing on Prc's entry into the world economic system suggests that information technology resulted in manufacturing chore losses in the United States, in particular during the steeper job losses subsequently 2000 (Autor, Dorn, and Hanson 2016).

Of course, globalization has conferred a number of benefits for workers. Merchandise has lowered consumer prices, helping increase existent wages; moreover, exports can be an important source of productivity and wage growth (Bernard et al. 2007). However, U.S. imports are more likely than U.S. exports to be produced past low-skilled workers (Katz and Murphy 1992; Borjas et al. 1997), suggesting that trade may put downward force per unit area on wage growth for low-skilled American workers.

While globalization plays a role, most inquiry finds that it is not principally responsible for the pass up in labor demand experienced past depression-skilled workers (Helpman 2016). Technological change that raises the relative productivity of high-skill workers is some other important cistron (Goldin and Katz 2010; Autor, Katz, and Kearney 2008).

The manufacturing sector provides an instance of how technological progress can affect particular groups of workers. As seen in figure 4b, U.S. manufacturing output has increased considerably since 1973—most doubling in 40 years—while manufacturing employment has fallen sharply. This increase in manufacturing productivity has been accompanied past a shift from low-skilled to high-skilled workers in the manufacture (Berman et al. 1994).

Globalization and technology have brought great gains to American workers as a group, only their benefits have been unequally shared. They accept likely contributed to worsening labor market outcomes for low-skilled workers, helping to explain the stagnation in their wages.

Fact 5: Wages have grown for women and fallen for men.

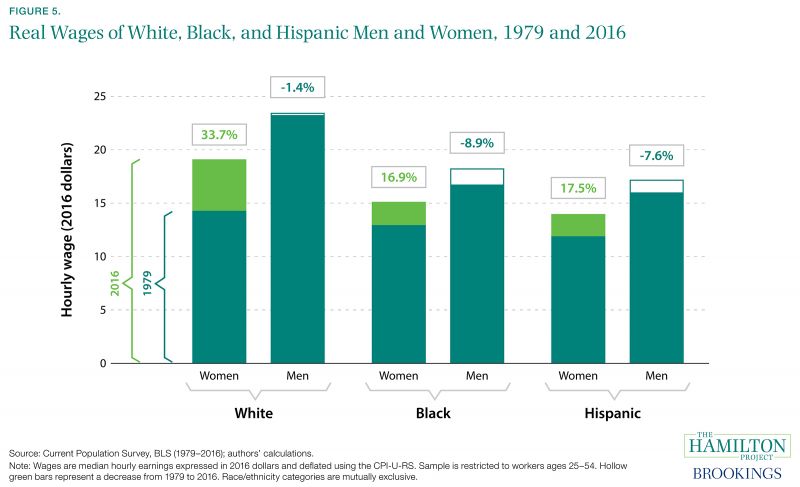

Wage inequality is closely linked to differences in earnings by gender and by race/ethnicity. In both 1979 and 2016, not-Hispanic white men earned more per hour than any other group. Relative to non-Hispanic blackness and Hispanic men, white men increased their advantage over that period. But within each racial/indigenous grouping, men's wages have been stagnant or falling over time.

Even so, women have gained ground. White women take seen a wage increase of 34 percent, while blackness and Hispanic women have both experienced growth at around 17 percent. Women's wage levels remain beneath those of men, just the gender wage gap has narrowed over time.

Much of this narrowing was driven past the increasing educational attainment of women. By the early 2000s, 25- to 54-twelvemonth-old women had surpassed men in both four-year and advanced degree attainment (authors' calculations; non shown). The segregation of men and women in different occupations—which accounts for some of the gender wage gap—macerated at the same time that more than women obtained college degrees (Cortes and Pan forthcoming).

The gap in wages by race/ethnicity has proven harder to close. Labor market place discrimination is an important role of this design (Bertrand and Mullainathan 2004; Charles and Guryan 2008), as are pre-labor market differences in the experiences of whites and people of color (Altonji and Bare 1999).

Fact vi: Declines in the real minimum wage and union membership take affected wage growth.

Although the increased demand for educated workers explains much of the ascension in wages for workers in the upper role of the wage distribution, other factors account for wage stagnation among lower-income workers as well equally the broader decline in the labor share of income.

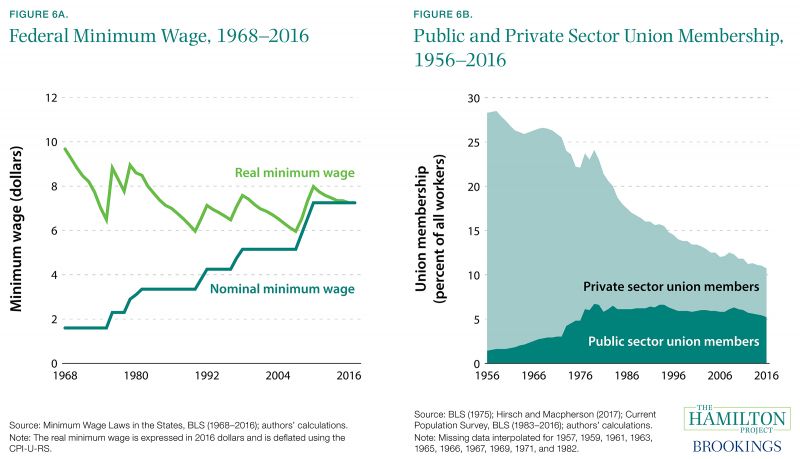

One such factor is the refuse in matrimony membership. In 1956 well-nigh 28 percentage of all workers belonged to a spousal relationship; in 2016 that number was a piddling more 10 pct. This decline has occurred principally amidst individual sector workers, only five percent of whom now belong to a marriage. With this fall in union membership has come an increment in wage inequality (Menu 2001). The spread of other labor market institutions—such as noncompete contracts, and no-poaching and bunco agreements past firms—could too be contributing to weaker worker bargaining ability.

In addition, turn down in the real minimum wage has limited wage growth among low-wage workers. Autor, Manning, and Smith (2016) observe that changes in the statutory minimum wage were one gene in explaining changes in the ratio of median wages and the 10th percentile of the wage distribution. Similar to the style that men were unduly affected by declining union membership (Fortin and Lemieux 1997), the falling existent minimum wage in the 1980s disproportionately affected women, accounting for as much as half of the ascension in wage inequality amidst women (Autor, Manning, and Smith 2016).

More recently, increases in country minimum wages appear to be raising wages at the bottom terminate of the wage distribution (Gould 2017). Raising the minimum wage could affect millions of workers with wages at or somewhat above the minimum wage (Kearney and Harris 2014).

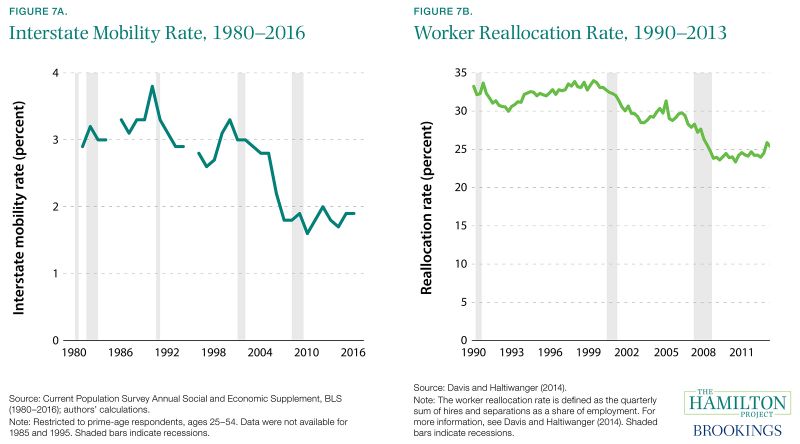

Fact 7: Workers have become less likely to motility to a different state or to a different chore, reducing wage growth.

In contempo decades American workers accept become less likely to move to new places and to new jobs. Since 1990, interstate mobility—defined as the percentage of U.S. residents who move from one state to another in a given year—has declined by half, from 3.viii percentage in 1990 to less than 2.0 pct in 2016 (see effigy 7a). The labor market is a primary driver of migration, accounting for about half of interstate moves (BLS 1980–2016 authors' calculations). Part of the explanation for the long-run reject in geographic mobility lies in economic diversification: as each region of the country attracts a wider range of industries, the regions go more alike, allowing workers to discover jobs locally that they would have otherwise had to relocate to obtain (Kaplan and Schulhofer-Wohl 2017).

At the same time, workers are switching jobs less frequently and staying longer at the jobs they have. Figure 7b shows the decline in the worker reallocation charge per unit, defined as the sum of hires and separations, both divided by total employment. After remaining approximately level through the 1990s, the rate subsequently savage past about one-quarter. Worker reallocation rates have fallen for male person and female workers, as well every bit for workers of all ages, didactics levels, and states of residence (Davis and Haltiwanger 2014).

Macerated worker mobility might have an of import negative impact on workers' wage growth. Under normal economic conditions, chore-to-job mobility generates well-nigh 1 percent earnings growth per quarter. During recessions, this mobility declines and workers find it more hard to climb the job ladder into college-wage positions (Haltiwanger et al. 2017).

Public policy has probable contributed to the decline in both geographic and task-to-job mobility. Occupational licenses and noncompete contracts, for example, often hinder workers' ability to pursue economical opportunity outside of their current state and employer (Starr, Bishara, and Prescott 2017; White House 2015). In addition, land-utilise restrictions that reduce new housing development contribute to a reduction in worker movement to high productivity areas, limiting both productivity and wage growth (Ganong and Shoag 2017).

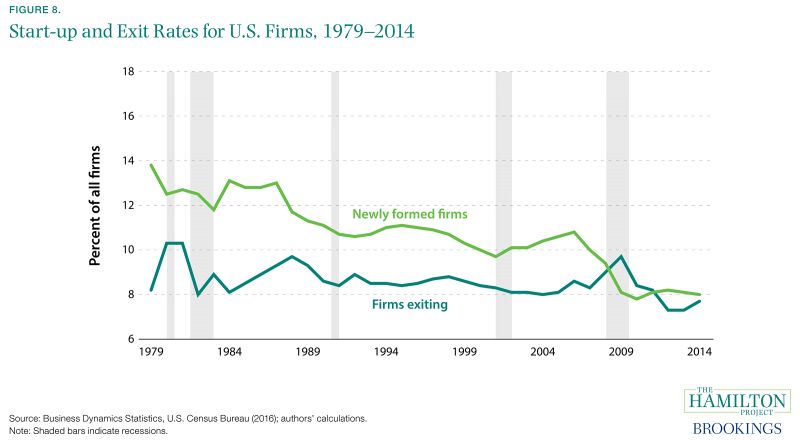

Fact 8: Business formation and closings have declined.

Over the past several decades, start-ups take become increasingly deficient, with their share of all firms falling from 14 pct in 1979 to 8 pct in 2014. At the same time, the rate at which businesses close down has declined slightly over the long run. Unsurprisingly, the Great Recession was a period of temporarily elevated concern closings and depressed business concern first-ups.

Immature firms at present employ a smaller share of workers. Davis and Haltiwanger (2014) explain that the decline in young, fast-expanding firms has contributed to falling business dynamism and job churn.

More firms exited than entered during the Dandy Recession, and the typical firm's historic period has continued to rise (Davis and Haltiwanger 2014). Researchers have linked the turn down in the number of immature firms to increased business consolidation and decreased rates of population growth (Hathaway and Litan 2014). The fall in start-ups and young firms has a negative impact on wages. Immature firms tend to poach workers who are making job-to-job moves, which can help them to climb the job ladder and achieve stronger wage growth (Haltiwanger et al. 2017). As the average historic period of firms increases, chore churn falls (Wiczer 2014), resulting in diminished economic growth (Lazear and Spletzer 2012).

Diminished dynamism can too impede the reallocation of resources to high productivity firms; recent research indicates that the decline in dynamism in the tech sector occurred at the same time every bit the refuse in productivity growth (Decker et al. 2016). This lower productivity growth in turn restrains wage growth.

Chapter ii: How stiff has wage growth been since the Great Recession?

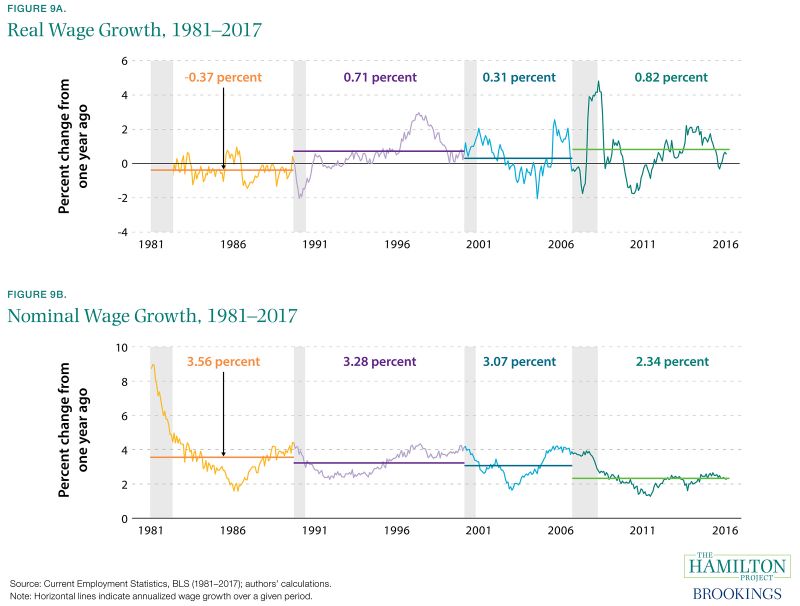

Fact 9: Inflation-adapted wage growth was higher from 2007 to 2017 than it was during previous business cycles.

By comparing with the previous three business cycles, aggrandizement-adjusted wage growth since 2007 has been relatively strong. It is slightly ahead of the growth seen during the 1990s or 2000s business organization cycles and is notably college than growth in the 1980s. Figure 9a plots year-over-year growth in real average hourly earnings for production and non-supervisory workers, showing trend growth separately for 1981–90 (-0.37 per centum), 1990–2001 (0.71 percent), 2001–7 (0.31 percent), and 2007–17 (0.83 percent). It is important to note that this recent real wage growth followed years of stagnation and has been accompanied by rising inequality, likely making information technology feel bereft to many workers.

All the same, low inflation during this virtually recent menses generates a starkly unlike story for nominal wage growth (i.e., wage growth without any adjustment for inflation). Figure 9b shows that nominal almanac wage growth has been only 2.4 percentage since the start of the Smashing Recession, contrasting with nominal wage growth higher up 3.0 percentage in each of the previous business cycles.

Typically, nominal wage growth rises later in expansions and falls during recessions, while real wage growth may bound up or downwards with variation in aggrandizement. But the virtually recent expansion has seen little uptick in nominal wage growth, peculiarly in dissimilarity to the previous iii expansions.

Fact 10: Labor marketplace slack has declined during the recovery from the Smashing Recession, though some probable remains.

While in the long run real wage growth depends on productivity and the distribution of gains from productivity, over shorter time horizons wage growth can exist determined past the supply and demand for labor. When at that place is extensive slack in the economy—such as during a recession or the early phase of a recovery, when labor and capital are underutilized—wage growth tin be temporarily lower. At these times, there are more unemployed workers and hiring need is low, both of which put downward pressure on wages.

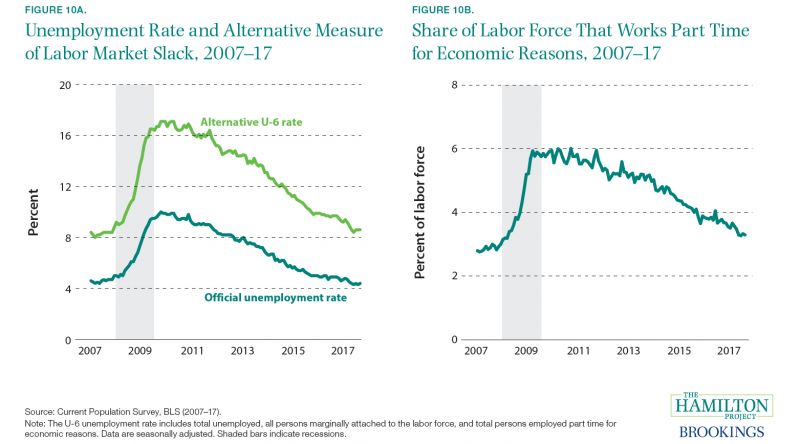

The sizable slack in the U.S. labor markets early in the Great Recession likely put substantial downward pressure on wage growth for a number of years. By many measures, labor marketplace slack is now at roughly its prerecessionary level. The unemployment rate was 4.three percent as of July 2017, with several states experiencing tape lows. The alternative U-6 rate—a broader mensurate of unemployment that includes the unemployed, people working part time who would like total-time work, and those who would similar a task just are not actively looking (marginally attached workers)—is also at its everyman level since the Great Recession. A number of other measures tell a similar story, including the rise in workers' job quits, job openings rate, and the length of time required for firms to fill task vacancies (Yellen 2017). Still, at that place might be slack remaining in the labor marketplace: the number of people working part fourth dimension for economic reasons remains elevated relative to the precrisis flow, inflation remains unusually depression, and the employment rate of prime-age workers remains below its prerecession starting point.

Diminishing slack in the labor market generally means that employers must pay college wages to attract workers (Krueger 2015). Wage growth for less-educated workers is particularly sensitive to changes in labor demand (Katz and Krueger 1999), but thus far the large reduction in slack has not been accompanied by dramatically higher nominal wage growth.

Fact 11: Recent labor productivity growth has been irksome, restraining wage growth.

The period start with the Swell Recession has been characterized by some of the weakest growth in labor productivity (1.one percent annually) for a business organisation cycle in the postwar era (Sprague 2017). Yet, this tendency of reduced productivity growth emerged prior to the recession. Productivity growth began to slow in 2004, after the 1995–2004 technology nail, and has since slowed even more during the recovery from the Great Recession (Fernald 2015).

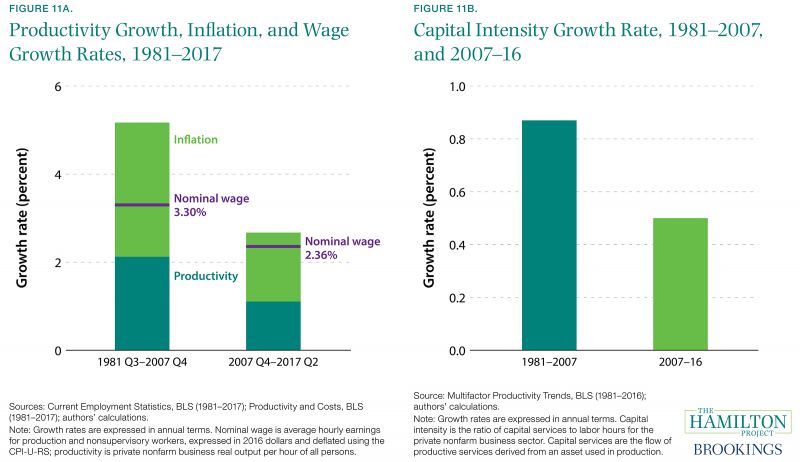

Given the importance of labor productivity growth for facilitating wage growth, the slowdown in productivity growth in the United States has likely had negative effects on workers. Figure 11a depicts real productivity growth, inflation, and nominal wage growth for the periods 1981–2007 and 2008–17. Wage growth from 1981 to 2007 conspicuously lagged backside inflation plus productivity growth, highlighting the fact that productivity growth is not e'er sufficient for wage growth. Lower productivity growth since 2007 could be limiting the upside to wage growth. As shown by the bottom portion of the stacked bars, real productivity growth fell from two.ane to 1.1 percent. When added to aggrandizement (the top portion of the stacked bars), this gives a sense of the maximum sustainable nominal wage growth rate.

Weak investment growth—equally depicted in figure 11b—has played an important role. During the recovery from the Cracking Recession, growth in capital letter intensity (the ratio of uppercase services to labor hours) has fallen far brusque of historical norms, even contracting in 2011 and 2012. This ways that workers take less capital to work with, which impairs their productivity and wages.

The reduction in capital investment growth is thought to be closely related to the broader slowdown in Gdp growth (Council of Economic Advisers 2017 chap. 2; Furman 2015). As the economy continues to heal from the Great Recession, capital investment should increase, providing the foundation for sustained wage growth.

Fact 12: In recent years, measured wage growth has been depressed by changes in the workforce.

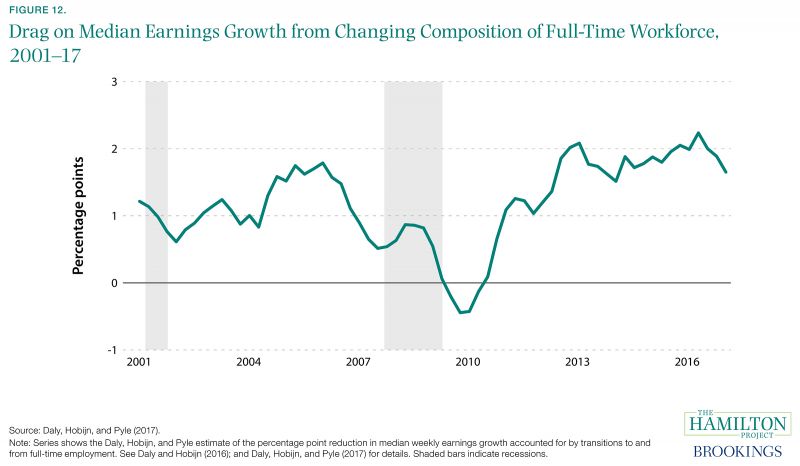

Measured wage growth reflects changes in wages for continuously employed workers as well as changes in the composition of the workforce. That latter component of wage growth evolves every bit workers of varying wage levels enter and exit employment. At any given time, those exiting employment might have wages that are quite different from (and typically higher than) the wages of those who enter, causing overall wage growth to differ from the wage growth of workers who were continuously employed (Daly and Hobijn 2016).

Figure 12 displays the drag on median weekly earnings growth from the changing limerick of the full-fourth dimension workforce. In normal times, entrants to full-time employment have lower wages than those exiting, which tends to depress measured wage growth. During the Great Recession this issue diminished substantially when an unusual number of low-wage workers exited full-time employment and few were entering (Daly and Hobijn 2016). Afterwards the Great Recession ended, the recovering economy began to pull workers dorsum into total-time employment from office-fourth dimension employment (see fact ten) and nonemployment, while higher-paid, older workers left the labor force.

Wage growth in the heart and later on parts of the recovery cruel short of the growth experienced past continuously employed workers, reflecting both the retirements of relatively high-wage workers and the reentry of workers with relatively low wages. In 2017 the effect of this shifting composition of employment remains large, at more than 1.five percentage points.3 If and when growth in total-fourth dimension employment slows, we tin expect this effect to diminish somewhat, providing a boost to measured wage growth. Given that the gap has been roughly stable for the past five years, this composition event does not explain the lack of pick-upwards in wages as the labor market has tightened, but rather helps account for the overall tiresome footstep of growth in nominal wages during the unabridged recovery.

Fact xiii: Wage growth during the Keen Recession occurred amid elevation earners, but has since go more broadly shared.

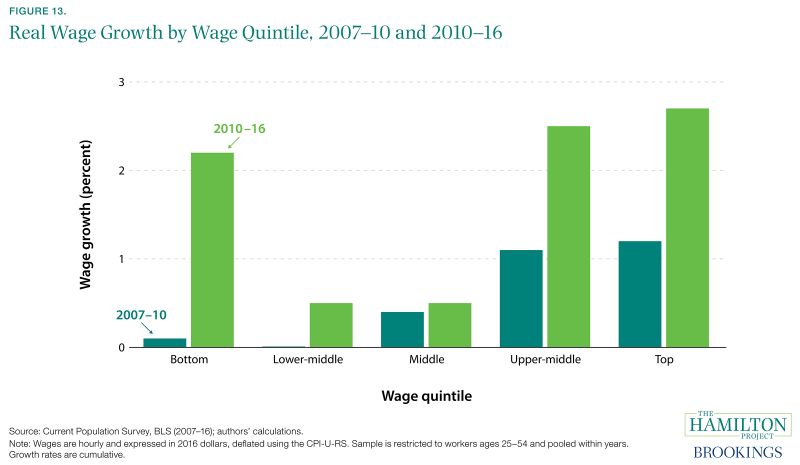

During the Swell Recession workers with wages in the bottom iii income quintiles—sixty percent of all workers—experienced limited or no growth in their wages. For the top-earning twoscore percentage of workers, wages increased past more than than 1 percent over the same period.

Since 2010, however, wage growth has accelerated for all workers, and particularly for the lowest-paid workers. 1 caption for recent wage growth among low-wage workers is the legislated increase in the minimum wage in many states (Gould 2017). Comparison changes in state minimum wages from 2015 to 2016, Gould (2017) shows that workers in the 10th percentile experienced real wage growth of 5.2 pct in states that raised their minimum wage, compared to an increment of 2.5 pct in states that did not.

Despite the more rapid increase at the lesser of the income spectrum, along with continued growth at the meridian, wage growth for workers in the centre quintiles has connected to be sluggish. 1 possible factor limiting wage growth in the recovery is that, during the recession itself, wages were to some extent prevented from falling (due east.g., by employee reluctance to take wage reductions). If wage rigidities prevented wage cuts, employers might have limited raises during the recovery to rebalance (Daly and Hobijn 2015). Nevertheless, as time passed subsequently the end of the recession, the wage-dampening influence of this gene weakened.

Source: https://www.brookings.edu/research/thirteen-facts-about-wage-growth/